by R. Todd Johnson

The businessmen believe that they are defending free enterprise when they declaim that business is not concerned “merely” with profit but also with promoting desirable “social” ends; that business has a “social conscience” and takes seriously its responsibilities for providing employment, eliminating discrimination, avoiding pollution and whatever else may be the catchwords of the contemporary crop of reformers. In fact they are–or would be if they or anyone else took them seriously–preaching pure and unadulterated socialism.

Quote from Milton Friedman, September 13, 1970, The New York Times Magazine, “The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase its Profits.”

Forty years after the publication of Milton Friedman’s still oft-cited piece in The New York Times Magazine, the epic battle continues around whether businesses should produce positive social results other than jobs and wealth. And yet, as we approach the end of a tumultuous decade – when markets and economies have fallen, when Soviet and Chinese communism have given way, more or less, to market economies, when social entrepreneurship shows signs of success, when the gap between the world’s richest and the world’s poorest has continued to widen, when strong, vibrant middle classes have begun emerging in Brazil, Russia, India and China, and when demand has sharpened the focus on a future of resource constraints – the prevailing attitude of American free-market capitalism remains that corporations should exist primarily or even solely for wealth creation.

One thing has changed, however. Today, passionate capitalists ask more and more often, “Why can’t a corporation do business, for good?” Why does a free-market, capitalist system of economics seem so inept at providing for the long-term good of shareholders, as well as the long-term good of the planet and its inhabitants, and why doesn’t it seem to be helping in the hard places of the world, where nearly half of the world’s population is living on less than $2 per day?

Given the 40th anniversary of Milton Friedman’s piece last month, it seems appropriate that we stop and ask: “What have we learned over the past 40 years?” “What would Milton Friedman say if he were writing a similar piece today?” and “Has our thinking (and would his thinking have) changed as a result of the last 40 years of experience?”

Corporate Social Responsibility: A Brief History

Today’s concept of a “social entrepreneur” may seem new in the world of American business. Yet, even the term “corporate social responsibility” (or sometimes “CSR”), that emerged with a vengeance on the business scene forty years ago, was itself preceded by an ancient history reflecting concerns around the impact of business on people and the planet. For example, nearly 5,000 years ago, societies had commercial logging operations as well as laws to protect forests. The Hammurabi code developed in 1700 B.C. required that builders, innkeepers or farmers be put to death if their negligence caused the deaths of others, or resulted in a major inconvenience to local citizens.

In some ways, these examples foreshadowed today’s CSR ideals of pursuing wealth creation without harming the planet or its inhabitants. The point is to acknowledge the longstanding societal policy decision that business owes a responsibility for a greater good – as a quasi-citizen of society – to living within a set of prescribed norms that would be enforced by government. This prescribed normative behavior, acknowledged by Friedman himself as necessary, seems reasonable given that American society has granted business great freedom (perhaps greater freedom than anywhere else in the world) to pursue its wealth creation ends as a quasi-citizen, with the Supreme Court recently going so far as viewing businesses as a “person,” entitled to the protection of the Bill of Rights and its Constitutional right to free speech through unlimited expenditures in political campaigns.

The industrial revolution brought into sharp relief the impact of business on the lives of individuals and the environment, often with direct consequences, giving rise to an environment of greater regulation, where workers, air, water, land and animals were all the objects of protection. The industrial revolution also gave rise to an attitude of “corporate paternalism” in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, resulting in wealthy industrialists dedicating some of their wealth to support philanthropic ventures. These sentiments flourished in the writings of capitalists like Andrew Carnegie, founder of U.S. Steel, who believed that in order for capitalism to work, the “elite” class must practice charity and exercise good stewardship. To him, capitalism regularly failed the “have not’s” of society, so the rich, through institutions such as churches or community groups, were required to do so. Carnegie went even further, advocating that the wealthy consider themselves stewards of their property “in trust” for the rest of society.

In some respects, Friedman’s piece reflects this same mentality when he ends by saying “there is one and only one social responsibility of business–to use it resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits so long as it stays within the rules of the game,” thereby providing the most money to the individual shareholder to exercise their individual right to be charitable and “do good.” Although no one denies the great value resulting from charity, the real question is whether this reflects the greatest aspirational goal for business – making some people wealthy beyond description in order that they may provide for the rest of society. And even if we conceded this to be the highest aspiration, shouldn’t we stop and ask periodically, “How is business doing?”

By the 1920’s, discussions about the social responsibilities of business had evolved into what we can recognize today as the beginning of a modern CSR movement. In 1929, the Dean of Harvard Business School, Wallace B. Donham, commented in an address delivered at Northwestern University:

Business started long centuries before the dawn of history, but business as we now know it is new – new in its broadening scope, new in its social significance. Business has not learned how to handle these changes, nor does it recognize the magnitude of its responsibilities for the future of civilization.

Perhaps never before, as in this past decade, have these words carried so much relevance for so many. Enron, WorldCom, banks and other financial institutions that are “too big to fail,” climate change, the rapid growth of human trafficking around the world (directed not only at lucrative sex trafficking, but also cheap labor for growing global supply chains), child soldiers in areas of conflict that strangely coincide with maps of growing water resource constraint, the loss of lives in mining disasters both in America and China, oil spills of catastrophic dimensions in the Gulf of Mexico and in China, and the list goes on – all these experiences of the past decade conspire to give Donham’s voice the prescient ring of truth 80 years later.

The Failure of the Enforcement Model

Many argue that the disasters of the past decade point to a need for bigger and better regulations and tougher enforcement of the rules on the books. This proscriptive approach to creating better business behavior has been tried for more than 80 years and compelling arguments can be made that it has failed miserably. Just look at our system of regulations, where we’ve spent billions of dollars regulating and enforcing, yet still end up with disasters taking a toll on human life and the environment.

Why does this continue to happen?

Business schools typically teach future business leaders the concept of “capture theory” – the idea that regulators, over time, become the captives of the regulated. This theory suggests that regulated businesses influence, more than any person or group, the selection of the regulators, the drafting of legislation, the drafting of regulations and, through lobbying and election spending, the budget allocation for enforcement. Thus, the proscriptive approach often produces a “dive to the bottom,” setting up a lowest common denominator of acceptable behavior and a mindset of minimal compliance as normative, rather than creating aspirational goals for business to achieve. As a by-product, we encourage an adversarial system, both of rulemaking and of enforcement between business and other stakeholders, resulting in litigation where short-term compromises of reformed behavior, coupled with big payouts to plaintiffs, plaintiff classes and plaintiff lawyers, often result in little systemic change.

In this respect, it seems useful to understand how we might create a corporate model that encourages some aspirational behavior beyond “lawsuit avoidance.” What if directors were not so risk averse and were not so regularly advised by the most risk averse creature known to man – the staple at board meetings – a lawyer? What if directors felt they would be rewarded for encouraging innovation in a company – innovation that focused on long-term benefits – even if that innovation failed to produce short-term monetary returns, because it lived up to the stated purpose of the company?

The Failure of Binary Thinking

Unfortunately, entrepreneurs setting up companies and seeking to apply the lessons of the past and implement a new code of aspirational behavior for the future of their business are left choosing from among the same bad choices that existed forty years ago. Until recently, available corporate forms left entrepreneurs with an “either – or” calculus: either adopt a corporate form that maximizes doing well (wealth creation), or adopt a corporate form that maximizes doing good (most often, the so-called “non-profit”). In Milton Friedman’s words:

In a free enterprise, private-property system, a corporate executive is an employee of the owners of the business. He has direct responsibility to his employers. That responsibility is to conduct the business in accordance with their desires, which generally will be to make as much money as possible while conforming to the basic rules of the society, both those embodied in law and those embodied in ethical custom. Of course, in some cases his employers may have a different objective. A group of persons might establish a corporation for an eleemosynary purpose–for example, a hospital or a school. The manager of such a corporation will not have money profit as his objective but the rendering of certain services.

This separation of doing well from doing good represents the great legacy of corporate paternalistic public policy decisions, embodied in the federal tax code designed originally to give tax benefits to the rich who participated in Carnegie’s charity and stewardship ideals. Today, after more than 100 years of experience, we can all see (and hopefully admit) that this binary thinking for business models often produces unhealthy and unintended consequences, both at the local and global levels.

Unintended Consequences and Externalized Costs

At the local level, binary thinking leaves the start-up entrepreneur with two possible forms of capital to access – the $1 million investment or the $10,000 charitable contribution. I remember my first meeting seven years ago with John Sage, founder of Pura Vida Coffee – a fair trade, shade grown, organic coffee company that gives back to the coffee growing regions of the world – when he described his efforts to obtain funding from sophisticated private investors. By his account, investors were all focused either on their “return on investment,” or the social impact and leverage of their charitable donation. As John put it, “when I explain the possibility that in Pura Vida their money might do both – offering a possible return on investment, while also providing funding for at-risk children in coffee growing regions of the world – they respond by saying simply ‘you’re making my head hurt,’ and then move on to the next item on their desk.”

As a result, the entrepreneur is forced into accepting an investment, allowing for scale and the hiring of professionals, but risking the mission of impact in favor of profit, solely or primarily, in order to satisfy an expected return on investment. Or, the entrepreneur can make the scale and the speed of the undertaking secondary goals to the consistency of mission by establishing a non-profit.

The binary thinking of corporate paternalism also presents a dangerous dynamic globally, resulting from the export of our special brand of capitalism. Traditionally, Americans are known for two remarkable qualities: our entrepreneurial spirit and our heart for helping the poor, the disadvantaged, the hungry, and those in distress (whether as a result of disaster or conflict). And yet, the bifurcation of our organizational structures leaves much of the world with a view that we are hypocrites.

In her recent book, The Economics of Integrity, journalist Anna Bernasek reviews the value of integrity in business. Speaking clearly about how our economy is built on trust, she attempts to measure how businesses that build trust and integrity have brands, products, services and financial results that distinguish them from competitors. Unfortunately, her list of examples is relatively small, and the companies noted seem to be the exceptions, rather than the rule.

Perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised that more businesses don’t pursue the blended values of doing well and doing good. Our lack of a corporate form that encourages both values, results in the exportation of an entrepreneurship that most often reflects the value that “greed is good,” and equally often creates devastating results in the harvesting of natural resources and minerals, the utilization of cheap labor, the sale of goods in the developing world that cause physical harm, and the manufacture of goods in places with limited or lax environmental laws, all in the name of reducing expense and increasing margin. That, after all, is the greatest social responsibility of business.

Then, when disaster strikes, the biggest and best non-governmental organizations (many of which are U.S.-based, founded and funded) go to work spreading the goodwill of the American people. Unfortunately, these efforts are often spent cleaning up the negative results, indirect consequences or failures of businesses, resulting in reinforcement of the view that Americans are hypocrites.

Even worse, this goodwill often comes at the expense of business opportunities for local people in the developing world.

Outside of direct relief aid and some of the amazing health and education research and development, much of what is done in the developing world through non-profits and non-governmental organizations (or NGO’s), could actually be accomplished through a business model, even if it would be harder to obtain investment funding. Instead, someone begins selling tax subsidized and donor subsidized water pumps in Africa. They could sell the pumps for a profit, without a tax subsidy or donor subsidy, but funds are easier to raise through tax deductible donations rather than through the rigors of proving out the business model for investment dollars. Selling the pumps through a non-profit has the positive result of increased deployment of inexpensive water moving technology in the developing world to aid rural farmers, but the negative results of both killing markets for future indigenous entrepreneurs attempting to sell water pumps at a profit and locking potentially valuable distribution channels into non-profit organizations making it difficult for use by for-profit organizations.

Even worse is the buy-one, give-one or “BOGO” model that has become increasingly popular for companies here in the United States seeking the halo effect of helping places like Africa. Whether it’s shoes, flashlights or computers, in Africa you can find numerous retail products produced by U.S. companies (often in Asia), where the purchase price paid by a U.S. consumer includes the cost of donating a second such product to Africa.

“What’s wrong with that,” you might ask? On the surface, nothing.

Take shoes, for example. Africans need shoes. In fact, shoes are critical to issues of health, nutrition, education, healthy pregnancies and much more. Child malnutrition continues to afflict most children in Africa who take in too few calories and burn too many (often fetching fuel or water) for healthy growth and the mental stimulation required for an adequate education. And when young women are malnourished, their under-developed bodies often lead to complicated pregnancies and, in the worst cases, to still-born deliveries after three days of labor and fistulas that leave the women childless, incontinent, and ostracized by a community and family that does not understand.

So how does that have anything to do with shoes?

Let’s take a look at one country – Ethiopia – and let’s assume that you could provide the approximately 60 million rural Ethiopians who are living on less than $2 per day with the appropriate levels of nutrition for healthy development, but no shoes. In all likelihood, those Ethiopians would still be malnourished, and under-developed due to the prevalence of worms and other parasites, all of which could be treated with medications, but that would continue to recur if rural Ethiopians walk around barefoot stepping in animal droppings.

So it’s clear – shoes are important in rural Ethiopia.

Now comes the real issue: Should shoes be donated by Western companies, or should they be produced in Ethiopia and sold locally?

This is where the BOGO model, although well intentioned, appears to be hindering long-term, sustainable solutions for Africa. As long as rural Africans might potentially receive free shoes donated by a U.S. shoe company, why would they want to pay for shoes? And, as long as rural Africans are unwilling to pay for shoes, how can local African shoemakers hope to have a flourishing local business?

And that’s before we ever get to the biggest issue facing the African entrepreneur.

Last year, while in Addis Ababa, I visited with my friend Sammy, an Ethiopian entrepreneur. Interested in how his new SMS content platform business was going, I asked Sammy about his greatest challenge. His answer was simply, “The NGO economy.” Sammy noted what should have been intuitive to me after my many trips to Africa: Africans are naturally entrepreneurial – many have been making something from nothing all their lives, just to stay alive. But what Sammy said next rocked my world.

“Africans don’t see a reward, other than survival, from being entrepreneurial. Specifically, they do not view entrepreneurship as a means for lifting themselves out of poverty. Rather, what they learn at a very early age is that they can make good money, if they learn to speak English well and then maybe, just maybe, they can get a job driving for an NGO. In a few years, if they play their cards right, they might be able to land an NGO job as a project manager and even advance further.”

Sammy’s point was simply this. As a struggling businessman creating new start-ups in Africa, he could not compete with what NGO’s were paying for some of the best and brightest. And even worse, he said, “by the time the NGO’s are done with them, there isn’t an ounce of entrepreneur left.”

These examples should leave us asking questions, such as:

• Are we concentrating too much funding to philanthropies that are killing places like Africa?

• Why can’t we build for-profit enterprises designed to produce a reasonable or even dramatic return for investors, while at the same time producing a flourishing of human life and the environment, and maybe even help in some of the hard places in the world?

• Why can’t ventures in the form of for-profit corporations be funded to scale and compete for the best and brightest, without a risk of losing a mission that might include a flourishing of people and the planet?

• Why is it that the blending of the values of caring for people, caring for the planet and achieving profitability, seems so hard for entrepreneurs choosing a for-profit model?

• Can anything be done within the existing corporate and finance frameworks to change that dynamic?”

And, most relevant to this article,

• What would Milton Friedman say?

Milton Friedman’s View: Shareholder Democracy or Utilitarianism

As the Ayn Rand acolyte and objectivist, Roger Donway has noted, there are only one of two ways to understand Milton Friedman’s views on social responsibility: either he was an advocate of shareholder empowerment and democracy, or he held a utilitarian view of corporations and the deployment of investment capital.

The first view suggests that corporate executives are only expressions of a bounden duty to “shareholder-bosses [who have a] right to be self-interested money-grubbers, desiring only ‘to make as much money as possible while conforming to the basic rules of society’?” If this is correct, then those advocating greater shareholder rights to remove directors or access proxy statements with proposals regarding corporate conduct would seem to have a friend in Friedman.

In which case, what happens when the shareholders and investors want to both create wealth and ensure that those efforts involve no negative impact on people or the planet? Even better, what happens when those goals become more aspirational, such as a corporation whose investors desire that their management both makes money and helps people and the planet to flourish? As we note below, these goals are difficult to accomplish with the corporate forms available today, but it would seem from Milton Friedman’s point of view, such a corporate purpose should be permitted and, in fact, encouraged, when that is what the shareholders desire.

In the alternative to Friedman’s own words, Donway argues that Friedman backed away from this view of listening to shareholders in later years and instead began justifying corporate profit-seeking (to the exclusion of other social responsibilities) on the basis of utilitarianism. In Donway’s words:

The perspective of “social responsibility” looks upon a free-market system not as the social expression of individual rights, but as the means by which society organizes the use of “its” resources so that they are employed in the most valuable way — “valuable,” presumably, in accordance with some utilitarian standard. Within this system, shareholders are, yes, justified in pursuing the maximization of their wealth (through the work of their servant-executives). But they are so justified only because their pursuit of profit happens to be a means employed by society for the general, collective good. In effect, society is employing “its” selfish shareholders to make certain that society’s goods are deployed in the most efficient and value-producing manner. That, according to Friedman, is the overarching justification for the selfish behavior of those who participate in business.

Assuming for a moment that Donway’s perspective on Friedman’s view is correct, then one might rightly ask why Donway’s calculus of “value” applies to only one societal resource – monetary wealth – when costs to other societal resources (such as the environment and the health and well-being of individuals, both of which impact societal wealth creation either directly or indirectly) have long been seen as costs externalized in our present system. Instead, it seems quite plausible that someone deploying this utilitarian equation might rather propose achievement of a blended or integrated set of values, especially where shareholders, investors and entrepreneurs are collectively seeking aspirational goals of building businesses that optimize the creation of wealth and the flourishing of individuals and the planet. In fact, these collective aspirational pursuits by society could well reflect a rational collective decision to choose deployment of capital to achieve these blended values, as the most effective, value-producing means for capital investment.

Time for the “For-Benefit” Corporate Model

When I was younger, my father repeated a Winston Churchill quote that I paraphrase here:

“If you’re not liberal when you are young, you have no heart.

But if you’re not conservative when you are older, you have no brains.”

Even though that line still begs a chuckle today, as I’ve gotten older, I’ve come to realize that it is really a great lie.

Why?

Because it allows lines between “smart” and “stupid,” and between “good” and “bad” to be drawn between us, rather than through each one of us individually. The lie of the quote permits me to place you on one side of the line or the other, and helps me avoid responsibility for what I do that is “stupid” and “bad.”

Basically, Churchill’s line lacks integrity. It’s cute, yes, but it doesn’t really help me understand the truth.

The same is true today of the pervasive idea that a corporation can either “do good” or “do well.” The idea simply lacks integrity. When we separate doing well and doing good, in a person, an organization or a corporation, the completeness or “whole” no longer exists – there is a lack of integrity, in the traditional sense of the word’s meaning.

Take U.S. tax policy, for example, that rewards entities for “doing good” with deductions and tax exemptions. Corporate philanthropy (up to 10% of profits), expenditures on research and development, and employee health care, among others, all receive tax deductions as a result of public policy decisions designed to encourage that behavior.

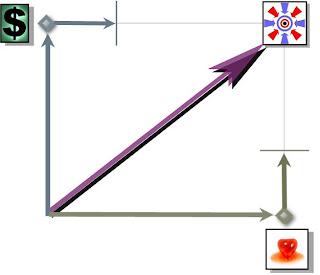

Even further, so-called “non-profits” represent another corporate form, this time for maximizing “doing good,” rather than creating wealth. Thus, for-profit corporations “do well” by creating private wealth, and non-profits “do good” by creating other social benefits. This binary thinking of doing good versus doing well produces two systems that can be represented simplistically on an x-axis/y-axis as follows:

where the $ sign represents the highest point on the axis for creating private wealth (doing well), and the ♥ represents the highest point on axis for creating a social benefit (doing good). Our figure shows that a classic “for-profit” entity (typically a subchapter C corporation or a limited liability company) scores high on the doing well axis, but near the bottom of doing good, whereas a non-profit or tax-exempt corporation scores the opposite: high on doing good, but near the bottom for doing well.

Of course, that last statement is overly broad. Corporations have long undertaken corporate philanthropy; supporting the arts, education and contributing to programs to alleviate the conditions of poverty. But corporate philanthropy does not represent the universe of ways in which corporations have a positive social impact. Companies employ people, produce efficiencies in the use of capital, improve lives, help alleviate poverty and starvation, not to mention create wealth (both for executives at the top of a corporation, but also workers holding equity in IRA’s, mutual funds and pension funds). Yet even further than all this, CSR programs are entering their third decade of wide-spread adoption, with more and more positive measurable impact on communities, extreme poverty, and reducing negative stress on the planet and the environment.

Interestingly, this movement of for-profits toward doing good, in addition to doing well for their shareholders, and the movement of non-profits toward doing well, in addition to doing good, does not represent the result of some grand orchestration. Rather, in a very real sense, the behavior of each organizational type has been, and continues to be, a movement towards the natural point of integrity, or wholeness and completeness – in the upper right-hand corner of the earlier diagram.

And yet, both forms have their limitations.

For example, corporate philanthropy is limited – because tax policy only rewards a deduction for up to 10% of corporate profits donated to philanthropy. But would directors find protection under the rubric of the business judgment rule if they decided to give away 50% of corporate profits to help at-risk children in the developing world? Certainly, at some point, directors find themselves exposed to arguments of wasting corporate assets. Thus, the law has a barrier on how much good a typical for-profit corporation can undertake, at least in terms of giving away profit. So too, most states limit special purposes that corporations may undertake, if it creates a trade-off to the primacy of maximizing returns for shareholders.

Likewise, capitalistic strategies of earned income have their limits for non-profits. The typical charity may earn profit to support charitable activities, even income unrelated to their charitable mission, so long as they pay taxes on the income. But at some point, the earned-income strategies of a non-profit threaten a test of “substantial relatedness” to their charitable mission, so that too much earned income could jeopardize its charitable status. This, in turn, limits efforts for non-profits to achieve sustainable models and forces them back into the fundraising circuit annually.

And yet, one look at the diagram above, begs the question: “Why not create an entity unfettered by the “for profit” and “non-profit” rules, thereby establishing corporations for broader benefits, or what I like to refer to as “for-benefit corporations”? Permitting a form that allows the entrepreneur to build an organization that aims directly for the “for-benefit” sector represents the shortest distance between two points.

Unfortunately, until recently, no system existed that brought integrity to the corporate organizational form.

This year, both Maryland and Vermont have adopted laws and California is considering similar legislation allowing corporations focusing on profitability, to also elaborate purposes such as creating a flourishing environment for the people working for the corporation and for other constituents, such as the community in which the corporation does business, as well as the planet.

Imagine: Businesses seeking profit and the well-being of the planet and its people. People, planet, profit. It may seem idealistic to many, but there are companies already achieving some success without the “for-benefit” corporate form. The time has come to give these like-minded entrepreneurs and investors a corporate form that actually works towards their blended value pursuits.

For those concerned that directors and management might hide poor economic performance behind corporate purposes where results are harder to measure, all three of the statutory options require transparency far beyond anything previously on the books, thereby permitting far greater opportunity for investors and consumers alike to weed out the “green-washers” – those companies who are determined to spend time, money and effort on good marketing, rather than on really doing good.

Likewise, the statutes do not permit companies to opt-in or to opt-out of the “for-benefit” form without shareholder approval, typically at a supermajority level. Thus, businesses adopting this form will have an explicit understanding between shareholders and management that transcends the model of the traditional selfish shareholder.

Contrary to Milton Friedman’s fears that such a pursuit could only occur at the government’s behest, thereby representing a form of socialism – or government control of the means of production – these statutes create a voluntary framework by permitting entrepreneurs and investors to opt-in to the “for-benefit” corporate form, rather than forcing it on anyone. Ultimately, this means that the markets will determine, over time, whether such a form is viable. Either businesses adopting this form will attract capital, or they won’t.

I think Milton Friedman would be proud of such a free market approach.

R. Todd Johnson is a partner at the law firm of Jones Day, where he heads their Renewable Energy and Sustainability Practice. He co-chairs a working group in California that drafted Senate Bill 1463 and is seeking the implementation of “for-benefit” corporate laws in other states. The views expressed in this column are solely Mr. Johnson’s personal views, not the views of Jones Day or its clients, and the information provided as to his affiliation with Jones Day is solely for purposes of identification and may not and should not be construed to imply endorsement or even support by Jones Day of the views expressed herein.

© R. Todd Johnson, 2010. The thoughts, ideas and words expressed in this column are excerpted, in part, from a forthcoming book by R. Todd Johnson, titled “Business for Good” and are the property of R. Todd Johnson and may not be otherwise used or reprinted without his express permission.